Beaten, Perplexed but not Crashed: Informal Workers in the Face of COVID-19

Crises come, and crises go, but none has held the world at ransom like the COVID-19 pandemic. Global economies were endangered and some of the most advanced health care systems started to crumble. Experts have predicted a roll-back in some of the gains made towards gender equality as women worked day and night to uphold their societies without a care for themselves. In Uganda, panic shopping got the best of us. Now that the situation appears to be returning to normal, what if we asked you if you received the government posho and beans that was promised as relief food for vulnerable citizens? Hold that thought, what if we asked you whether for one moment during the lockdown, you stopped and thought about the plight of the woman who sells you fruits at the market, or the one selling roadside gonja, (roasted plantain) or even your boda guy? If you did not, relax, it is not something we will hold against you. We were all trying to survive a pandemic.

However, now, you can stop and think about the women in the informal sector – women who were further marginalized by the pandemic, women whose lives were threatened to the very core. We bring you stories of four women, from downtown Wandegeya who were kind enough to share their COVID-19 experiences with us, in the hope that action will be taken to make their situation better. These are stories of struggle and compromise, told amidst tears and sudden bouts of laughter, because they have nothing left to do about their situations. They hold hope close to their chests, envisioning a brighter future ahead as they continue to navigate the systems that have forgotten about them.

Catherine

The burden of fending for the family consequently fell on me which meant that I had to think innovatively, in the middle of a pandemic.

My name is Catherine*. I come from Rukungiri but I live in Katanga and sell bananas on the street in Wandegeya. Before the lockdown was imposed, I had just restocked. The morning after the President’s address, I carried my bananas to Wandegeya and to my surprise, there were no cars. I had not listened to the address. I took my bananas back home and while we managed to eat some, the rest got rotten. Since my partner was also out of work, I could not get myself to ask him for the kameeza (money provided by male partner to look after the home) because I knew he did not have the money. The burden of fending for the family consequently fell on me which meant that I had to think innovatively, in the middle of a pandemic. For some time, we did not have enough food in the house and were forced to eat our little and hard-earned savings. After a while, we were able to receive the government food that was promised. We were relieved despite the fact that the food was of poor quality. Nonetheless, we were glad that we could put starving behind us.

In the midst of all this, the landlord was on our necks, demanding for rent. If we dared tell him that the president ordered for citizens not to be evicted, he asked if it was the president who built the houses. We had to pay in every possible way! Looking for alternative sources of income came with the risk of being accused of infidelity if I did not account for where I had obtained the money from. Some of my colleagues reported that their partners had turned to violence over similar issues. I noticed that domestic violence has been on the rise since the lockdown started. We tried and reported these cases to the village chairperson and women’s representative in vain. When they did not refer us to the police, they trivialized the matter as private and something to be settled confidentially between the two concerned parties. Where we succeeded in registering the case with the police, we would be asked for UGX20000 for them to carry out investigations. Where would we get this kind of money when we were struggling to put some food on our plates?

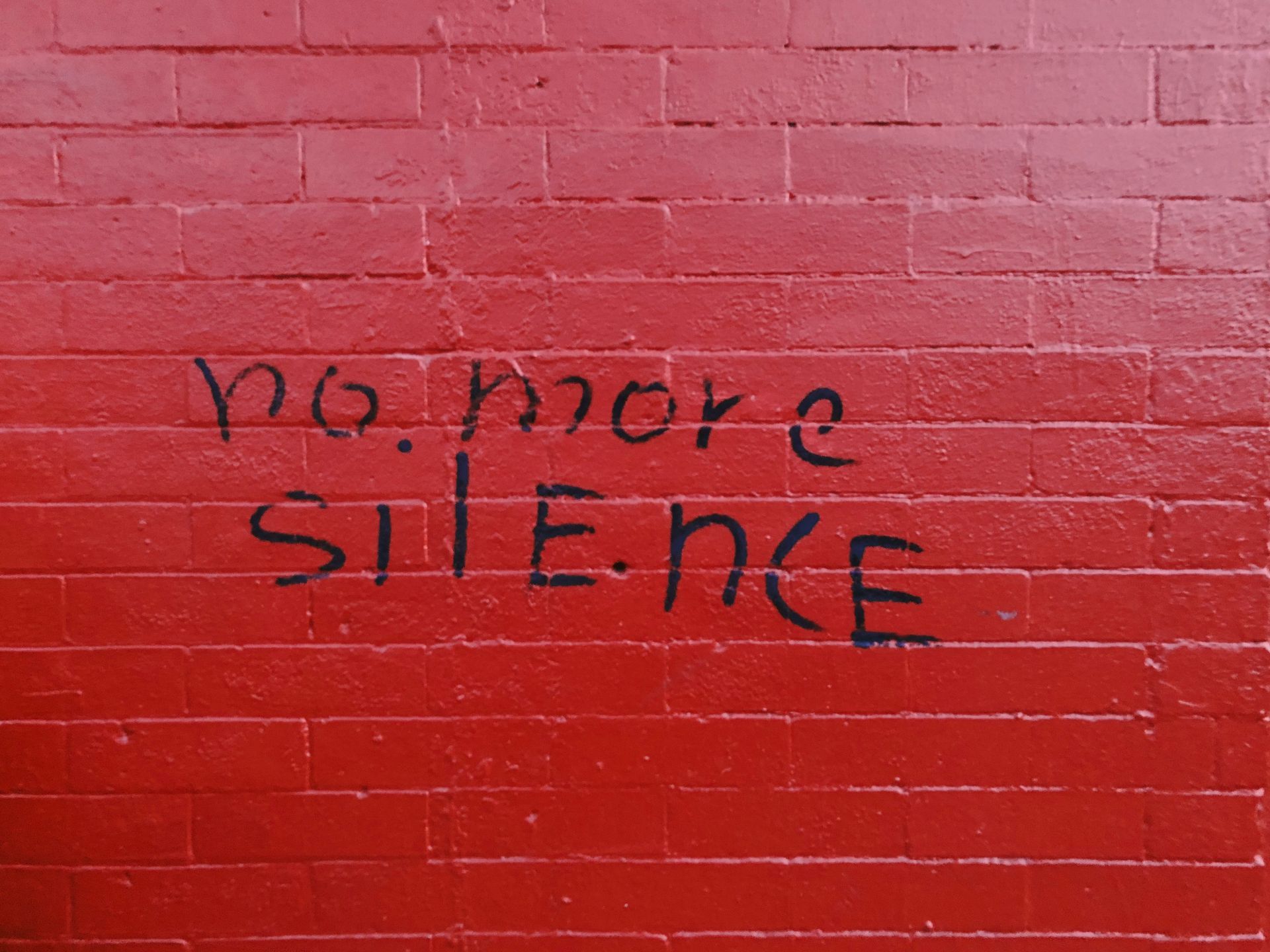

As the situation returns to normal, we are still struggling to get back to our feet. For some reason, we are not allowed to work. Between police and KCCA officials chasing us around, we are forced to work on the run. It is something we have gotten used to. When you spot them, you run away and return when they leave. I must do everything possible to take food back home at the end of the day. I cannot feed my children stories of the police grabbing my goods. The worst part about all this is that I am treated like an outcast in my own country. I pay my dues and yet I will not be allowed to sell my fruits on the street. Why would City Council agents treat me like an armed robber? Even before they treat me as such, why don’t they take time to find out why I work on the street, what situation has forced me to live that way before taking my hard earned money? If I could return to my village, I would. We have been forced to sell our property to pay these people so that they do not throw out our goods. I deserve better.

The worst part about all this is that I am treated like an outcast in my own country. I pay my dues and yet I will not be allowed to sell my fruits on the street. Why would City Council agents treat me like an armed robber?

In my opinion, it would have helped me better if the government gave me capital of say UGX100000 as opposed to handouts. We ate the 6kgs of posho and that was it, with the capital, I would have been able to start a new enterprise in response to the COVID-19 situation. The government also has the ability to support women’s groups and our investments to help us recover from the pandemic. At the moment, my biggest worry are my children. We do not know when schools will resume but when they do, school fees will be a major requirement. My dream has always been that my children will attain the level of education that I did not, and break that invisible curse over my people. What would make me extremely happy right now is if a good Samaritan came my way, I have heard of organisations that do so, and take that school fees burden off my chest.

Amina

My name is Amina* and I live in Kanyanya but I sell food in Wandegeya, by the roadside under those umbrellas that you usually see. I am one of the leaders of the Wandegeya Women’s Cooperative Society. This situation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has been doubly hard for me as a leader whom people constantly looked to for help and yet I had nothing to offer them either. At times, I managed to walk and go visit my members but it was shameful, to say the least, when I arrived empty-handed. People called me all the way from Nansana and Kyengera reporting that they had not received food and could not leave their homes not knowing that I did not know whom to ask for help either. When some of us approached the police, we were told that they (the police) had no authority over the food and were advised to go where the food was being distributed from. There, we were told to go to the Resident District Commissioner (RDC) who asked for letters from our Local Councils (LCs). When we took these, the RDC ridiculed us and told us that we were not the only people suffering and needed to be patient. The next time, we took seven women along with us and we were given just two bags of posho. Since people were almost starving, we conceded and took that. We had to live to face another day. Similarly, visiting health centres when one of us fell ill was a tug of war. We once walked to a health centre in Komamboga where we found long lines and left unattended to.

At times, I managed to walk and go visit my members but it was shameful, to say the least, when I arrived empty-handed.

The food was finally delivered and we are grateful that the government came through regarding that promise. But even then, not all members received the food and those who did could not afford the charcoal (fuel) to prepare it. I would find children picking sticks off the road to be used as firewood. Some went into draining channels looking for this same firewood. Meanwhile, back home, because men were looking to women to provide for the needs of the home, and women were looking to men, scuffles usually ensued with most of the injured being women. Relatedly, for our members whose husbands were spending their entire days at home, most of whom living in one-roomed houses, cases of domestic violence were reported for example in the form of marital rape. If the men needed sex, it did not matter that the children were watching and in most cases, the women protested which ended in rape.

Speaking of violence, we have faced a lot of oppression in our pursuit of a livelihood during this COVID-19 period. Normally, we would have to deal with Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) law enforcers chasing us around and while they have behaved this time round, we have had to face opposition from the police. We were mistreated by police officers who raided our stalls and made away with our goods. Later, we would learn that they took these and distributed them among themselves. Dealing with the KCCA is much easier because even as they chase us around, they endeavor to respect us and handle us like human beings. This is because we had an opportunity to meet with their leadership and air out our grievances. The leaders advised us to take note of their uniforms' IDs and report them. Once they confiscated our goods and when we reported these to the Mayor, our property was returned.

We were mistreated by police officers who raided our stalls and made away with our goods. Later, we would learn that they took these and distributed them among themselves.

Still on that, I wish that we did not have to pay bribes to be able to operate on the street. The situation is already hard as it is. While I understand that the KCCA license law is under review and will allow us to pay for a license to operate, it does not help our circumstances that the same KCCA agents demand for kitu kidogo (bribes) for us to keep our goods. We also come in search of what to eat. If I make UGX3000 in a day, that is what my children will eat. It is unfair for them to ask us to split it. As far as the savings group is concerned, at the moment, each member is looking at it as their means to recovery. Since the initiative was established only recently, membership is low and that means that savings gathered are minimal. Even with these, out of 70 members, about 30 are active yet each and everyone wants a share of the money. As a leader, how do I go about dividing these few funds among members? Our hope is that the government will look at the scheme as one to support and invest in.

My other plea to the government is for it to prioritize the needs of omuntu wa wansi (marginalized citizens) in service delivery. We have been extremely affected, more than the people who had the security of a monthly salary. We lost all our income. We know that programs exist to help people like us but those initiatives do not reach us. If the government looked into that and investigated it, perhaps we would be in a better place. Since we continue to remain invisible, my request to development organisations and women’s rights organisations is for them to amplify our voices at policy level. If I wrote a letter to the President and forwarded it through an NGO, he would pay more attention than if I dared approach him on my own. We fear, we are intimidated. Some of the places we go to ask for bribes, with NGOs, I know my issue will be heard. That is all I need, a listening ear.

Zaina

My name is Zaina* and I live and work in Wandegeya. I make katogo and sell it to passers-by. Sometimes, I sell oranges to supplement this. Well, this was all before, long before, the Coronavirus was declared a pandemic and we were forced to stay at home. At mine, the lockdown has been a depressing experience. It was imposed when I was sick and stuck in the house. My husband also lost his job and fell ill and as a result, we were two patients in the house. My legs hurt and I was unable to walk to the hospital which is quite far from where I live. This is an ailment I have nursed since October 2019. Back then, I could depend on handouts from my husband. My children were constantly hungry and it did not help that the neighbours always had something cooking outside. They were also not used to staying at home all day and reining them in has been a challenge. My landlord is always threatening to evict us for rent dues. Without a shilling in my pockets, I have nowhere to go. It is not like I can wake up and start trekking to my village with the curfew being enforced.

Between that, starving and making sure my children are still able to attend school, I am at a loss for what to do. I am grateful that the government offered relief food despite the fact that it took ages to get to us, and when it did, it was not the best quality. The schools communicated that learning would continue over TVs and mobiles phones, however, I have no smartphone and my TV set was stolen a while back when I was at work. Two of the children are in Senior One while the other is Senior Two. I did try to find ways of making money here and there to be able to at least provide for food. I asked colleagues to spare a few of their goods for me to sell, perhaps I will return the favour in the future. I am grateful that some of them agreed and while I am able to make UGX2000 or UGX3000 a day, it is not sufficient.

My landlord is always threatening to evict us for rent dues. Without a shilling in my pockets, I have nowhere to go. It is not like I can wake up and start trekking to my village with the curfew being enforced.

A number of times I asked the children to go to the streets and sell our products and even then, they are interrupted by the police and KCCA law enforcers. When they were not chased to the ends of the earth, our goods were confiscated. The children had to run to safety or risk being bundled up with the goods onto a police truck. That is if they did not demand for money that we already lacked. The oppression continued even in the confines of our homes. We live in a slum where the only space I have in my house is where I will sit and put my feet. It is surprising then that the LDUs when enforcing the curfew expected us to cook inside the house. Once they found me seated outside and forced me to go in with a burning sigiri (charcoal stove). Besides the heat, it is because of God’s protection that I did not burn the house.

The schools communicated that learning would continue over TVs and mobiles phones, however, I have no smartphone and my TV set was stolen a while back when I was at work.

If it had been up to me, I would have opted for capital instead of relief food from the government. I appreciate the endeavor but in my case, two bags of posho were damaged and when it came to the beans, I needed extra money for charcoal if they were to be well-cooked. The posho did not last a week. With capital, I would have made an investment and know that at the end of the day, all I had to spend was UGX2000 on pieces of matooke, (plantain) but with support for the next day. My situation was dire, it still is. I need all the help I can get.

Sarah

My name is Sarah*. When I am not hawking fruits and vegetables on the street, I am back home in Soweto Zone, Wandegeya. I am one of the leaders of the Wandegeya Women’s Cooperative Society. Work on the streets has been a challenge during the lockdown. We have had to deal with City Council issues daily. Once, we were beaten by the police and our goods taken and shared amongst themselves yet we were social distancing, had our gloves and masks on and even carried jerry cans with soapy water.

Some are not even real agents but simply conmen who prey on our fear of being arrested and end up extorting us.

We have constantly had to navigate LCs, police and City Council agents who have seemingly made it their life’s mission to oppress us. Some are not even real agents but simply conmen who prey on our fear of being arrested and end up extorting us. We have had to part with daily, weekly and monthly payments to be permitted to keep at our work, uninterrupted. Ask us why we do not oppose the payments and we will tell you it is because these agents will make our lives a living hell if we falter. Sometimes, we work in hiding to avoid paying these dues but rest assured that when you are discovered, you will pay up.

We are attacked on the streets and in our homes. Members of our SACCO underwent a domestic violence training previously and have used their knowledge on reporting to report cases of abuse. We have seen an increase in the number of incidences reported. Since both women and men were not working, and children were also stuck at home, families could no longer tolerate each other. This resulted in multiple acts of violence especially against women and children. The areas where we live are communal and when women denied men sex, you would find community members cheering the man on instead of rescuing the woman, an act that promoted marital rape. When we brought such matters before the police, we were told those were domestic issues and needed to be dealt with at that level.

Are we tired of being on the street? Yes. Are we tired of being beaten? Yes. But what to do, we have to survive.

My dream is that our SACCO could raise some funds out of a business and out of the profits, allow us to set us proper referral pathways to support our members in such situations and further raise awareness amongst ourselves. That is one of the challenges we set it up to address. Seeing as COVID-19 has stopped us in our tracks, we have to deal with current issues first. What we want now is for our working hours to be extended so that we can sell our merchandise to the people who leave their offices late. Are we tired of being on the street? Yes. Are we tired of being beaten? Yes. But what to do, we have to survive.

*Not real name